Issued by the American Humanist Association Board of Directors

July 17, 2013

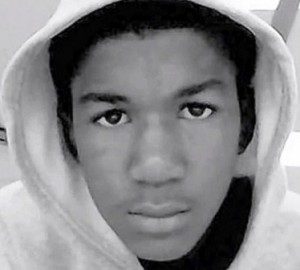

The trial of George Zimmerman did not end suspicion, nor did it provide great comfort. While the system worked in that there was public judgment rendered, it did little to quiet concerns regarding our ability to appreciate rather than fear difference. The moral of this story is similar to so many others – the often-deadly consequences of discomfort with racial difference. Nothing will bring back Trayvon Martin, and George Zimmerman will not spend any additional time in jail.

The trial of George Zimmerman did not end suspicion, nor did it provide great comfort. While the system worked in that there was public judgment rendered, it did little to quiet concerns regarding our ability to appreciate rather than fear difference. The moral of this story is similar to so many others – the often-deadly consequences of discomfort with racial difference. Nothing will bring back Trayvon Martin, and George Zimmerman will not spend any additional time in jail.

We are not in a position to read the minds of the jurors, and cannot know fully the strategies used by both legal teams. Any legal decision would have been met with both gratitude and frustration. So, the verdict will be embraced by some and seen by others as graphic representation of the deep problems with public life in the United States. It is also true that all will read it through the cultural worlds in which we live, and we will see in this verdict signs of both the problems and the promise of what we proclaim as a free nation with the best legal process in the world.

The killing of Trayvon Martin touches some of the most tender memories and experiences shaping our troubled relationship to race. Once again we have a tragic reminder that race and perceptions of race can be a matter of life and death; that our free society is still marked by a vigorous effort to mark off where certain bodies can go and where they should not be found without permission.

This situation, over the course of our history as a nation, has not been improved through religious rhetoric, doctrines and creeds that have often served to re-enforce such animosity by producing “inside” and “outside” groups. It doesn’t take much to cast these groups in terms of race. While we humanists believe humanism affords a way to wrestle with our national problems with reason over against theological doctrines and creeds, what we encounter with the death of Trayvon Martin fundamentally is a human dilemma requiring a commitment to collaboration and solidarity. Humanists must stand with all committed to justice and equality.

Our worst race-based inclinations are unfortunate and real, but they must not be allowed to rule the day, to determine conduct and to taint demands for equality. The flaws in our collective life exposed by this situation are tragic. Still, there is an opportunity here to challenge the ways in which race and its implications continue to matter – and to work toward a more life affirming society. There is no way to demand people like those who do not resemble them, but we must produce more humane ways of preventing that preference from destroying life, from taking away other Trayvon Martins.

Addressing our worst inclinations requires collaborative effort to better recognize the ways in which race and other markers of difference continue to impact individual and collective life. This is best expressed through renewed intention to make a difference, to now address the shortcomings of our collective life better than we have in the past.